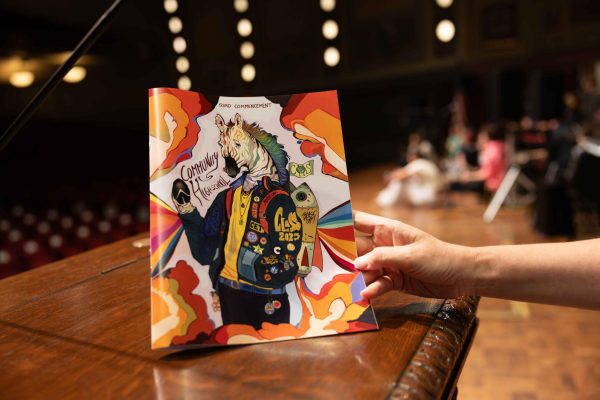

Slam Dunk

Clara Kaul and Carson Borbely celebrate their respective first and second place finishes at the 2015 CHS Poetry Slam.

As Kathryn Garcia, the first poet to read at the 2015 Community High School Poetry Slam, took the stage and began reading, the audience fell to hush. Hardly a noise was made through her poem before the applause at the end of her performance. Jeff Kass — literary arts director of the Neutral Zone, Pioneer High School teacher, organizer of city youth poetry slams and emcee of the event — walked back on stage. “You guys know,” Kass said, “you don’t have to be completely quiet during a poem.”

For the rest of the night, the audience took Kass’s words to heart. Particularly potent lines in a poem prompted a smattering of snapping or a few hollers. After the performance, poets were congratulated with thunderous applause. Most prominent was the reaction the panel of judges received. Any score below an eight or 8.5 on the scale from zero to 10 was met with resounding boos.

24 student poets participated in the CHS preliminary round of the Poetry Slam, competing to advance to the Ann Arbor final round. Each student given a chance to perform one poem to be scored by the five judges in a randomized order. The highest and lowest scores were dropped, and the other three averaged to create the poet’s final score.

Students who received higher scores moved on to a second round. After a small break of calculations, the judges advanced 11 poets to the next round: Carson Borbely, Maya Burris, Alice Held, Jacob Johnson, Clara Kaul, Sarah O’Connor, Eleanor Olson, Isaac Scobey-Thal, Violet Webster, Kaiya Wolff and Eve Zikmund-Fisher.

Scores from the first round were cleared, and each poet read a second poem. The highest scoring poets would move on to the city-wide round. This round, emotions ran higher; cheers were louder, as were jeers at the judges whenever a score fell beneath expectations.

A string of powerful moments characterized the second round. Borbely’s poem earned her wild screams from the audience and two perfect 10s from the judges. Up next was Kaul, who dedicated her poem to “the men who will someday hurt my sister.” She received a minute-long standing ovation, and before Kass had even read the judges’ scores, they all turned around, displaying the 10s they had each written on their boards. Kaul had gotten a perfect score from every single judge.

Johnson kept the event in full swing with his satirical and theatrical poem. Poking fun at the modern gun control debate, he performed as a man who was vehemently “pro-sword.” The audience once again rose to their feet.

After all 11 poets had read, it was clear that any further cuts would be agonizing; each student earned strong scores and a positive reception. Kass announced that seven students had advanced to the city-wide event.

First to advance were Olson, Scobey-Thal, Zikmund-Fisher and Held. Next, Kass announced the top three of the night. Johnson took third place, and Borbely was the runner-up. Finally, to nobody’s surprise, Kaul was announced the winner of the night. All seven poets gathered to the stage in triumphant celebration.

Many of the seven poets are quite experienced with slams, and some have moved on to the city round before. Zikmund-Fisher, however, had not read her poetry in public since fifth grade. She signed up not in hopes of going far, but so that other people could hear her poetry. “I didn’t think I’d do very well, but that’s not the point of the slam,” said Zikmund-Fisher. “The point of the slam is to read and to hear other people’s stuff.”

Zikmund-Fisher was shocked by the reception her poems received. “I was really surprised by how much people liked my poetry.” She now feels much more confident in her poetry.

All seven poets will compete on April 2, 2015, in hopes of advancing to Brave New Voices International Poetry Slam. Ultimately, though, the takeaway of the slams is not the numerical score assigned to a poem, but the opportunity of others hearing their voices. “I think a lot of people think, ‘Well, I could write something, but it’s not good enough,’” Zikmund-Fisher said. “No — just read it. And everyone will cheer for you because that is how a slam works.”