What happens to the American Dream when it becomes a nightmare?

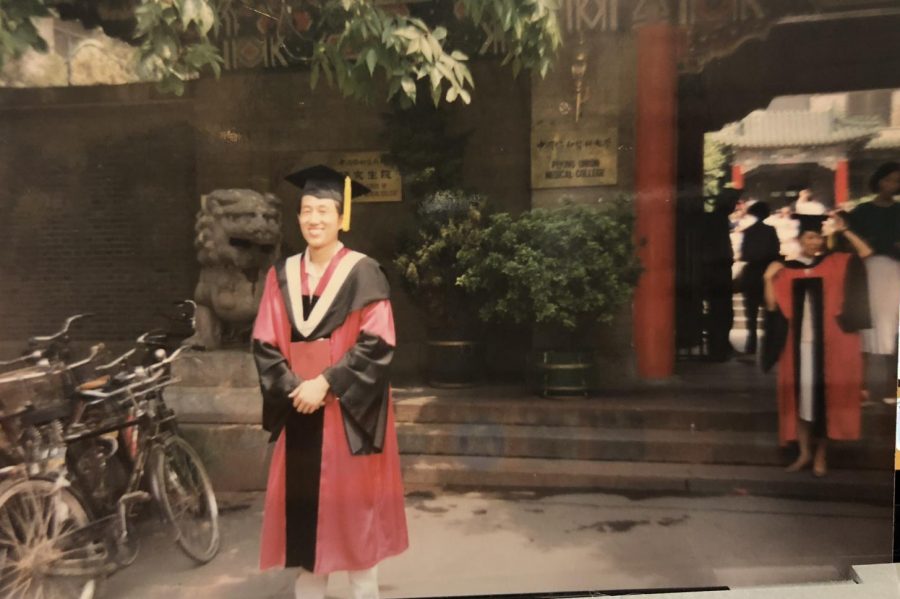

My father’s graduation from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences/Peking Union Medical College in 1992. He received a PhD in Molecular Biology, and his first daughter was just born that year.

Ann Arbor, 2006

I was five or six years old when one day, my parents and older sister came home from what seemed to be a random and mysterious excursion. They brought home three blue passports, with a gold insignia – patriotic eagle and all – on it. I put all our passports together when they arrived.

That day, I was left home alone for a reason: my family went to get their new American passports, after eight years of living in America. Finally, my family was the same as me: their old red passports from China were swapped out for the sleekest, newest edition of the American passport.

But I don’t remember the day in 1994 where my family boarded a plane to Chicago from Beijing, China, crying baby and all. I don’t remember the process of applying for a Visa, and I could try to rack my brain, but I still do not clearly remember a time where my family wasn’t considered American citizens.

Beijing, 1994

Working in the Department of Molecular and Biology and Chemistry in Beijing, my father had received an invitation from Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, for a scholarship sponsored by a research foundation to work at the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology there. The University issued a form for his J-1 visa, which was for work-related travel. My mother Wenyu and my then two-year-old sister Mengyao, nicknamed Yaoyao, were given J-2 visas. The caveat with the J-1 was that you had to come back to the People’s Republic of China to serve your country for two years. My father was sure he was going to go back to China after two or three years in Evanston; his life in China was certainly not going to stop for this trip to America, as he had just been promoted to Associate Professor at Beijing Institute.

Evanston, 1996

But the project he was working on got prolonged at Northwestern. His daughter began going to school, learning the English language and his wife got a job at the University of Chicago. It was clear that there were more factors that favored staying over leaving Evanston.

Back home, there were issues regarding raising their child: there were no housing offered in China. There was no commercial housing at the time, so you were only given housing based on your job. My family was currently living with my mother’s parents in their apartment – they would have to continue living like that if they moved back.

So there was no going back.

They initially had to find a lawyer to help them apply for a category of immigration called the National Interest Waiver (NIW). If a person and the job they were doing in America were offering great benefit to American people and ‘the nation,’ they could get a special permit to a green card.

If that didn’t work? Then the next plan was to head to Canada. There was no going back.

It took two months for my family to get that permit approved. It waived the need to serve your home country in the J-1 rule. After that was approved, they applied for green cards. And after that, my family waited several years before becoming citizens.

I was born in 2001, in the Illinois Masonic Medical Center; my family was given a birth certificate – which none of my past family members had received when they were born in China – celebrating their new seven-pound child and essentially their first taste of citizenship. But one kid didn’t grant them automatic citizenship: there was still work to be done.

Ann Arbor, 2018

“It is not that hard to come here, but to stay here is more difficult,” my father said in his dimly lit bedroom of our spacious suburban home.

He has lived in this home for the past 11 years, a townhouse for three years before that, and an apartment on Sherman Ave. in Evanston for years before that.

But he didn’t have a choice to stay, really. And neither do the immigrants who come here from across the border, on top of trains and through long treks. And neither do the immigrants who overstay their visits, get jobs, and try to stay.

How can you give away your future, your child’s future and everything you have when it is sitting right in front of you?

Legal immigration and illegal immigration are simply the results of the luck of the draw. If my parents were rejected by the NIW waiver, they would have been labeled as the lazy freeloaders of a foreign land. I hear the statement “they should have immigrated here legally,” as an offhand comment and seemingly easy option for those who find themselves as illegal immigrants.

There was no going back for my family, just as many immigrants we see crossing the border today. Staying meant the sweet taste of the McDonald’s baked apple pie and the image of an Ash Sunday on the small forehead at my sister’s first year at her Catholic school. It meant the night school my mother attended to learn English and her triumphant passing of the MCAT in English, alongside Americans who had known the language their whole life.

Immigration is bitter and unforgiving: new plans of slashing legal immigration in half, cutting the number of refugees we accept or tightening up our borders won’t solve any ‘problems’ we have with immigration.

Legal immigration should not be seen as better, or any different than illegal immigration. It is the same values, the same hard-working people and the same hopeful parents of children tasting their first words of English.