West Side Not Water Hill

David Malcolm noticed his neighborhood was changing.

It was when he was standing at the bus stop on Brooks Street, carrying a duffle bag. Malcolm noticed a man kept eyeing him as he walked toward his house. A few minutes later, a police car slowly rolled past Malcolm on the street. The policemen in the car were fortunately friends of his, and let him know they got a phone call reporting a suspicious black man that matched his description.

Or it was the time when his younger cousin got accused of stealing a woman’s lawn mower while walking from one property Malcolm’s family owned to another. He noticed police presence increase, and a change in the looks and attitudes of new residents.

These changes began in the 1990s, and this was not the West Side he had known since the ‘70s.

The West Side — now more commonly known as Water Hill — is the neighborhood off of North Main Street in Ann Arbor. Its main roads are Summit, Brooks and Sunset. It also includes the Kerrytown neighborhood around Community High School (CHS). It used to be a working class neighborhood with a high African American population, but starting in the ‘90s, the neighborhood began to undergo gentrification, which has recently ramped up.

Gentrification is the process of wealthier people buying homes for low prices, and renovating them, which increases the property value in the neighborhood. In order for gentrification to happen, there needs to be money. As a realtor, Malcolm has seen people buy houses in the West Side from residents at some of their worst times financially, renovate the old houses and sell them for almost double. Malcolm says that gentrification goes hand in hand with generational wealth. Many people pass their houses down to their children, which he calls “trust fund babies.” Depending on where a house is located in the West Side, and the type of renovations done, it can be sold for anywhere between $250,000 to $1,000,000.

He has noticed that most of the people moving into the neighborhood are white millennials in their thirties, or sometimes old retirees.The houses in the West Side were built in the ‘40s and ‘50s; some even date back to as early as the ‘20s. Most people move out of state, down south or to Ypsilanti.

“We used to be a neighborhood of people that look out for each other,” Malcolm said. “… as a kid, I couldn’t go three or four blocks away without my mom getting a phone call. Now I look suspicious, or I look like I’m doing something that I shouldn’t be doing, or I’m somewhere where I shouldn’t be.”

Malcolm does not believe gentrification itself is a bad thing, but believes that the problem is with the people left behind. It installs fear in the long-term residents in his neighborhood — like his 90-year-old neighbor who has buyers constantly knocking on her door, asking if she is selling her house.

The first African Americans that settled in Ann Arbor lived in the Lowertown area, around Broadway Bridge, where the original downtown of the village of Ann Arbor was located. Pontiac Trail, which feeds directly into Lowertown, was a stop on the Underground Railroad. African Americans that came to Ann Arbor were steered into certain neighborhoods, like the West Side, and segregated by being denied loans on houses.

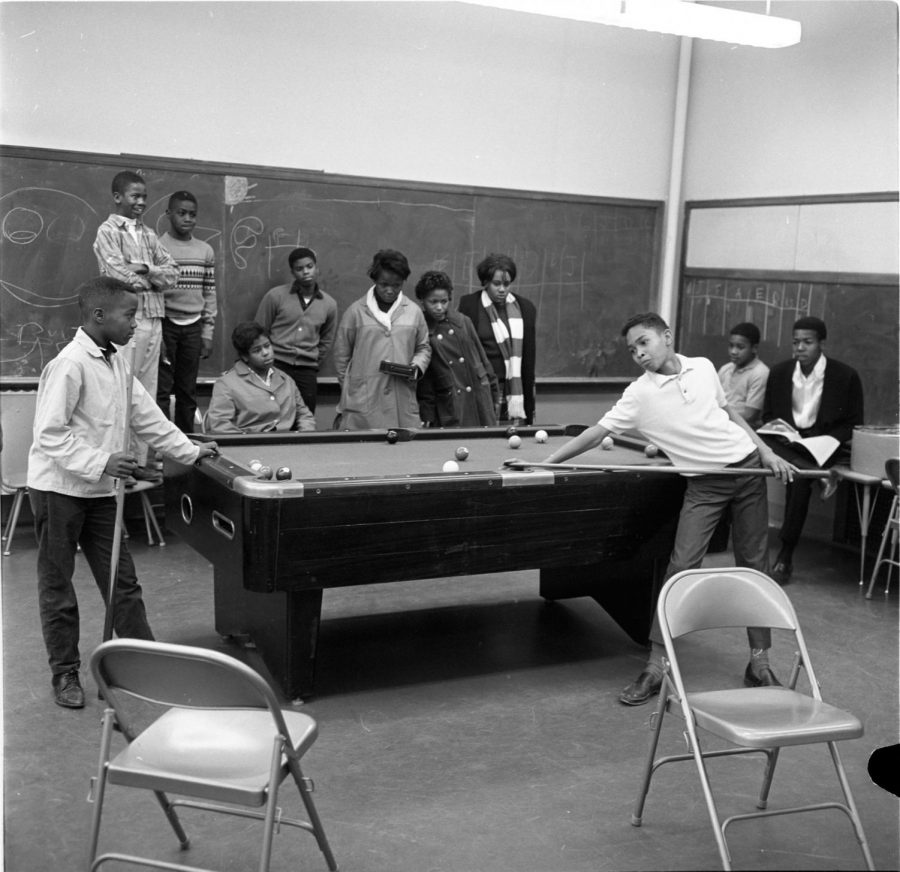

The West Side consisted of predominantly black families. Many of the children attended Jones School, which serviced grades kindergarten through eighth grade, and formerly inhabited the CHS building. Although Jones School was not a strictly all black school, the majority of its students were black due to housing segregation in the district.

A few long-term residents have moved out of the West Side, but Malcolm has been hesitant to leave. He figures that he could probably have a larger home somewhere else, but the West Side has been his home his entire life. He attended Mack School on Brooks Street and his parents attended Jones School. His grandfather built their house, and his family owns several other properties in the neighborhood. Malcolm’s family legacy is important to him, as his kids are following in his grandparents’ historical footprints.

“My family legacy keeps me [in the neighborhood],” Malcolm said. “I’m at a point in my life where I have to understand that I am actually my great grandparents’ legacy, not that house. Even though my granddad built it when he came back from the war, it’s a house at the end of the day. Would they want to see me there uncomfortable or not wanting to be there? Or would they want me to make good use of it and be happy?”

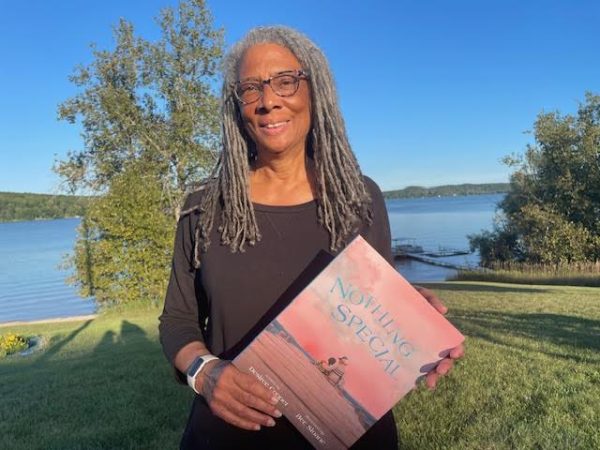

The neighborhood also has a strong legacy. Marlys Deen, a local historian for the African American Historical and Cultural Museum of Washtenaw County, also grew up in the West Side. She has witnessed the Civil Rights Movement and gentrification unfold in Ann Arbor: churches and community centers within the West Side had a large presence when she was younger.

The original community center for African American teens was the Dunbar Community Center, on the corner of Fourth Avenue and Kingsley. It opened as a center for black teens discriminated from the then-segregated YMCA, but closed in the ‘50s when the Ann Arbor Community Center on North Main street opened.

At the community center, people gathered for political meetings and held college fairs to help send African American students to school. Sometimes, discussions were held at night in large, multi-purpose rooms about the everyday discrimination members of the community faced.

Another Black community resource was the Elks Lodge, a large stone house that overlooks Argo Dam on Wildt Street and Sunset, and is Ann Arbor’s chapter of the black fraternity that started in 1899 in New York City. Ann Arbor’s chapter opened in the early 20th century, and has served the West Side for many years. It holds dinners and the house can be rented out for events.

“When I was growing up, I used to see the guys [who belonged to the Elks Lodge] riding around with the little funny symbols on their cars and stuff like that,” Malcolm said. “I really didn’t know what it was, but I just knew they were always great men. I knew that when I looked at them, they went to work, I knew that they went to church, I knew that they took care of widows and they took care of their neighbors… basically we had great men to look at as role models.”

However, as the West Side has changed, so has the presence of the strong neighborhood legacy. Malcolm has noticed membership of the Elks Lodge has dwindled from 300 members in the ‘60s and ‘70s to 30 members. The property is one of the most wanted on the market, cashing in around 1.75 to two million dollars the last time it was appraised. However, the legacy created by the community centers has left their mark on the West Side.

The term “Water Hill” is a fairly new name for the neighborhood. It was created by Paul Tinkerhess, a white resident, after the streets Summit, Brooks and Fountain. Some of the long-term residents, like Malcolm, hate the name Water Hill. To them, it’s always been the West Side.

A new neighborhood tradition is the Water Hill Music Festival, where residents use their front porches as stages for local bands to perform every first Sunday in May. One of the first years that the festival was held sparked controversy within the neighborhood with it’s placement of porta-potties on a sacred spot for long-term residents.

The porta-potties were placed on Belize Park, which used to be home to an old duplex. The young girl who lived in the second floor apartment babysat many neighborhood children after they came home from school at Mack. One day, the house caught fire. Deen believes that the girl was too afraid to jump out of the window to safety and too afraid to throw the child she was looking after down to neighbors trying to help. The two girls died in the fire.

A few long-term residents still remember this incident, and Malcolm has witnessed that the issue is still brought up at neighborhood meetings. To them, it was disrespectful to place porta-potties on the final resting ground of their friends.

Gentrification has changed neighborhoods on the local, state and national level. The history and people of gentrified neighborhoods are left in the dust, which is concerning to residents like Malcolm. He has noticed that gentrification is affecting public housing in Ann Arbor, and many neighborhoods in addition to the West Side are changing. Residents who move to Ypsilanti to escape gentrification in Ann Arbor also notice that it is happening there as well.

“I don’t mind that people are moving into the neighborhood, but I don’t like being a target of suspicion,” Malcolm said. “I don’t like my little cousins having the police called on them during the Water Hill Music Festival for stealing a lawn mower that belongs to them to go cut grass on a property that we own.”

For Malcolm, the neighborhood will always be the West Side, not Water Hill.