“The Favourite:” a triangulation of love, greed and war

In 1704, Abigail Marshall arrived at the palace of Queen Anne of England and took a position as a servant. Seven years later, she was appointed lady-in-waiting for the Queen, replacing Sarah Churchill, the Duchess of Marlborough, who had known the Queen since they were children and been one of her closest political advisors. Thus is the premise of director Yorgos Lanthimos’ eighth and newest film, “The Favourite.”

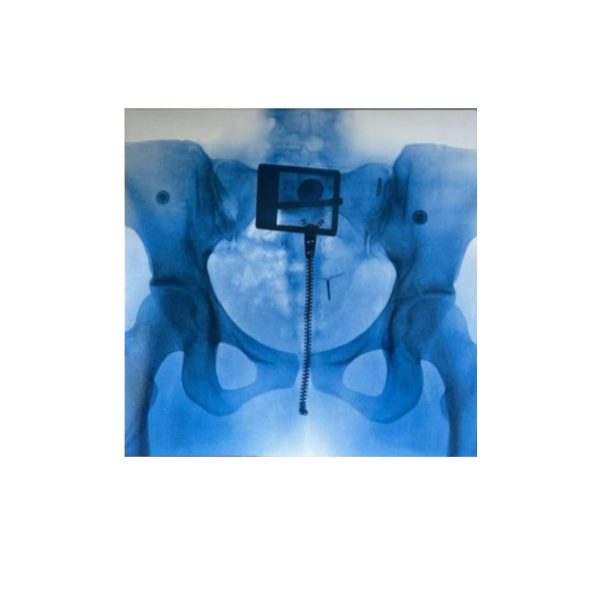

Lanthimos uses unusual camera angles and effects to further add to the eerie atmosphere of the film (a fish-eye shot of Abigail (Emma Stone) pushing Queen Anne (Olivia Colman) down a hallway curves across the screen, showing the physical dependence Queen Anne has on others; an up-close image of a man in a powdered wig laughing, roasted pig caught in his teeth and sauce staining his pink-blushed cheeks, is the only focus, displaying the laughable and near gruesome extravagance of the nobility).

The historical basis is refreshing, as is the immense presence of female power and complexity that can be lacking in films, particularly historical pieces. Although Queen Anne is portrayed as ridiculous and incompetent, she is undoubtedly always the most powerful person in a room, just as Sarah (Rachel Weisz) is always the smartest, and Abigail is always the most clever. Without being outwardly “progressive,” “The Favourite” tells the story of three strong female characters who are allowed to be compassionate and vulnerable without being martyrs, ugly and mean without being villains, and who are, ultimately, able to dominate a narrative they are often erased from.

“The Favourite” depicts the lavish life of the highest nobility in early 1700s England, a situation to which, granted, few can relate. But more deeply, it shows the intrinsic and often dark human desire to succeed, most aptly displayed by the character of Abigail. Abigail is introduced first when she is covered in mud and begging for a servant position in the castle. She seems innocent — an early scene shows her burning her hands after trying to clean bare-handed with lye — and is easily pitied; however, Abigail’s cunning and intensity, which is matched by the character Sarah Churchill, take the film from a historical comedy into a darker, unique analysis of the motivations that infest an individual who has no one for support but herself. Abigail shows how far she will go to achieve comfort: she would rather make herself bleed to gain an ounce of sympathy than suffer any more at the hands of others — “I’m on my side,” she says (in response to a parliament man who tries to make a deal with her, and asks her where her loyalties lie), “always.”

The movie is told in chapters, like a storybook. A time of transition is noted when a scene ends abruptly and white words fill a black screen, referencing a quote that will be said in the following few scenes — a technique that is contemporary and effective, as the audience leans forward to listen for the words that were just projected on the screen and to guess when they’ll come.

In fact, much of “The Favourite” is guessing at what will come next, and being invariably wrong (or at least in my case). The film is weird and unexpected, but that’s much of what makes it so appealing.

Ironically, almost every outfit is made up of only shades of black or white — a contrast to the murky and ever-changing world the characters are living in, but fitting to the setting of an English monarchy: built on rules and structure, attempting to paint a world black and white, and always failing.

I spent much of The Favourite in a state of confusion: I didn’t know whether I liked a character or didn’t; I couldn’t decide who I wanted to win, or what game they were playing. The ending scene was drawn out and chaotic, although every detail was obviously calculated. When the screen finally faded to all black, with the bolded title and then rolling credits, I still couldn’t accept it was over. Not that it was unsatisfying — I believe to some extent that it couldn’t have ended any other way — but rather it was… unexpected, like the entirety of the movie, like the entirety of real life.