COVID-19 Further Complicates School Funding Policy

CC Image courtesy of Robert Du Bois on Flickr https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/legalcode

*Note: These interviews took place in April. Decisions or information may have changed since then.

As the Michigan education budget is settled through the spring, a recent bill has sparked controversy about who should receive supplemental funding. House Bill 4048, signed by Governor Gretchen Whitmer on March 9, allocated one billion dollars in supplemental federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER), federal Governor’s Emergency Education Relief and state School Aid Fund (SAF) funds.

School districts that offered at least 20 hours per week of in-person instruction by March 22 and received less than $450 per pupil through the supplemental ESSER grants were also entitled to a share of $136 million in SAF money. Payments were equal to the difference between $450 and the district’s ESSER payment per pupil.

The Ann Arbor Public Schools (AAPS), which reopened for in-person after the March 22 date, was not able to receive the equalization payments and has received some complaints from parents and community members about the loss.

“It certainly is not indicative that we don’t care about the money or won’t work very hard to be excellent stewards of the funding opportunities,” said AAPS Superintendent Jeanice Swift. “But I do want to point out that the selection of the date and funding attached to that date occurred long after our decision-making and planning process and our decision-making process is based in the single priority of the health and safety of our students and staff. It’s not based on gaining some kind of legislative situation to achieve supplemental funding.”

The supplemental funding cannot be replaced with bond money and is not a part of the base budget. Supplemental funding laws are still being debated and passed by the state legislature.

The Michigan Education Association (MEA), which represents over 120,000 educators, also expressed opposition to the conditions in Bill 4048 in a response from April 13.

“Our members have been very vocal in opposing the provision in House Bill 4048 that ties additional school funding to those districts that offer 20 hours of in-person learning per week,” said MEA Spokesperson David Crim. “There are several other funding provisions in the bill that we do support, but tying that additional funding to in-person learning during a global pandemic is misguided and dangerous policy, especially now with Michigan leading the nation in new COVID-19 cases, and the number of cases in the 10-19 age group skyrocketing.”

A concern shared by some Michigan legislatures was that the bill would prohibit schools from pausing in-person learning in the case of a COVID-19 outbreak. Kyle Guerrant, the Deputy Superintendent of Finance and Operations at the Michigan Department of Education, says that schools can still temporarily close in the case of an outbreak without fear of funds being withheld.

“There was a concern, especially once the law was first passed, that there’s no mechanism in the law that if a district had to close that said, ‘Okay, if you had to close for a two week period, here’s how your funding would or wouldn’t be impacted,’” Guerrant said. “We are working with the legislature and seeking clarification from those that passed the bill. They said that that was not their intent to penalize schools that had to close due to public health and safety reasons. So nobody is being penalized for closing down after that March 22 date for some period of time.”

State Rep. Brad Paquette, a former teacher who ran on a platform of education reform and who worked on writing and passing the bill, says the funds aimed to incentivize in-person schooling for the districts that chose to offer it.

“We want to make sure that they [in-person schools] are supported if they were to make that decision so that’s why we are setting aside an extra $450 per pupil to support that because we know it’ll cost more to make sure that safety protocols are put in place and that people are supported in doing so,” Paquette said.

The federal government has passed three rounds of Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) for states during the pandemic. Only the first of those rounds did not require appropriation to be approved by the state legislature and could be immediately used. Later rounds have taken more time to deliver to schools as legislators debate appropriation.

“Billions of dollars are still stuck there, and a number of us, myself included, have been taking to the floor of the Senate to say, ‘Congress appropriated these funds for emergency purposes, the emergency is now,” said state Sen. Jeff Irwin. “Let’s get these funds working on behalf of our people.”

The ESSER rounds delivered $5.75 billion to schools, more money than seen in years. But the increase in funds meets an increase in costs as schools purchase computers, PPE and wifi hotspots to assist with hybrid or virtual learning, as well as past negative trends in education funding.

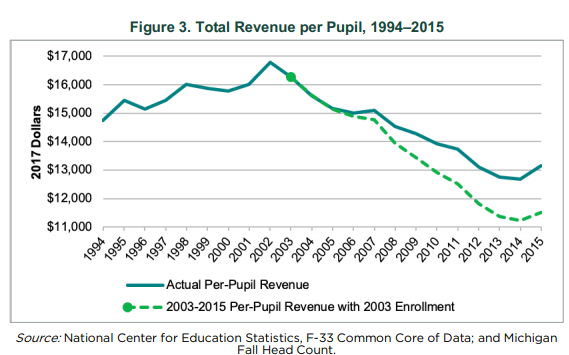

From 2002 to 2015, Michigan education funding declined by 30 percent, according to a 2019 study from MSU. Since 2002, revenue per pupil has steadily fallen.

A 2018 study by the Michigan School Finance Research Collaborative found that a $3.6 billion increase in education funding would be needed to meet their recommendations for an adequate provision of education. Michigan currently ranks 22nd in education funding and 23rd in spending.

“I think it’s an embarrassment to our state,” Irwin said. “I think it’s the biggest thing we’re doing to impair our own future here in our state because education and particularly K 12 education is the best investment we can make in our future prosperity.

But as revenue drastically increases due to pandemic emergency funds, some legislators are hoping to maintain the upward trend.

“There’s a hope that with these federal dollars that districts can provide the quality and the level of services for students and families throughout, from birth to 12th grade,” Guerrant said.“It’s an audition of sorts that will say, ‘hey look, for this time period we had these additional monies due to the pandemic. We were able to provide these services to children and families. What if we were funded properly? We could do this continually and not just when there’s a pandemic that has facilitated increased federal spending in our state.’”

As the budget continues to shift and be clarified throughout June, legislators look ahead to long-term costs from the pandemic.

“We know that coming out of this COVID year, we will need and want and expect to invest a great deal more in social-emotional support for our students, and academic support and recovery services for students with specialized learning needs,” Swift said. “We know that coming out of COVID is going to be a sustained effort over the years to come. So it is going to be important, and we will continue to vigilantly monitor budget processes so that we can ensure we’re supporting and serving our students in that catch-up and keep-up and move-up that will be a part of coming out of COVID.”