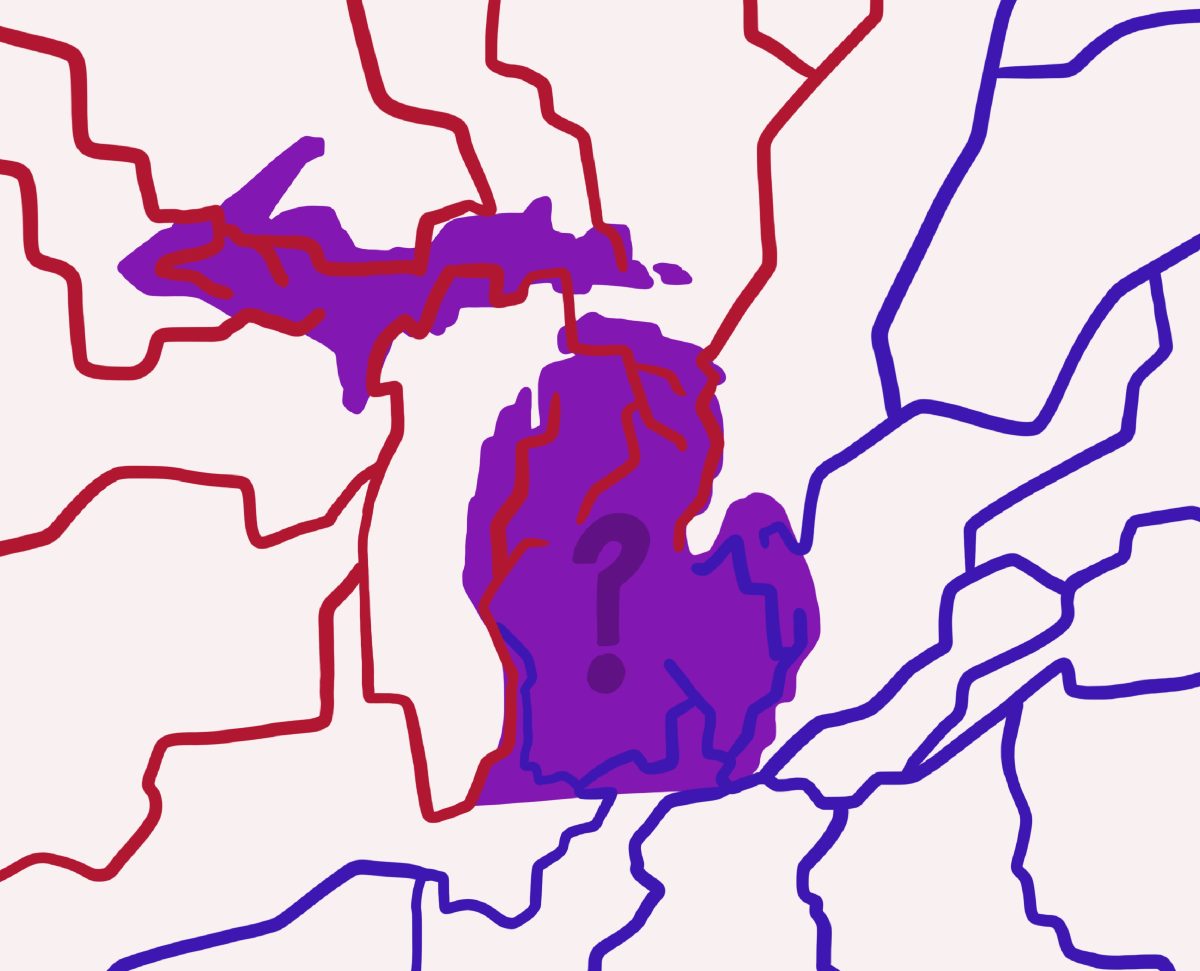

Michigan: A nearly 200-year-old state falls into a photo-finish for federal elections. Over ten million citizens find themselves divided over the 2024 presidential candidates. Younger voters hold the power to influence Michigan’s electoral votes, and preregistration can help minors prepare for their political impact.

Michigan Senator Sue Shink is a mother to two CHS graduates and a member of the Democratic Party. As a lifelong Michigander, Shink has witnessed the evolution of state politics to the current precipice.

“The way Michigan goes will decide our election,” Shink said. “And that’s true for a couple of different states, but it doesn’t take the responsibility off of Michigan to do everything we can to get people out to vote for freedom and for a future of opportunity.”

Shink is not up for reelection this year; however, she has been focusing her efforts on supporting other members of the Michigan Democratic Party to secure votes in their campaigns. She believes that this is crucial to continued civil liberties.

“It is really a choice between freedom and the United States going in a direction that has never gone, which is a dictator state,” Shink said. “And I know that sounds dramatic, but I believe that, and other people who have been involved in politics for many, many years believe that there’s so much at stake.”

Shink is a proud supporter of voter preregistration, a recent effort to increase voter participation among younger citizens.

A law passed earlier this year allows Michigan residents as young as 16 to preregister to vote. 16-year-olds can preregister online, by mail or automatically at the Secretary of State’s office as soon as they get their Graduated Driver’s License. They must be a United States citizen, a Michigan resident and not currency serving a sentence in jail or prison in addition to being at least 16 years of age to preregister to vote in Michigan.

Once preregistered, Michigan teens will automatically become active registered voters when they are 17 ½. To cast a ballot in any election, they must be 18 by the election day; however, they are still able to participate in absentee or early voting, just as long as they turn 18 by the election date.

“Voting is one of the easiest, best ways for us to choose the future that we want,” Shink said. She encourages all those who are eligible to register and to vote.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Michigan citizens ages 20 to 24 make up the second largest age group in the state. Younger voters are plentiful in the state, so how can they impact the 2024 election? Preregistration may be the answer to engaging younger voters.

Because Michigan is a swing state, a US state where the two major political parties have similar levels of support among voters, it’s viewed as important in determining the overall result of a presidential election — young voters could change which candidate gets Michigan’s electoral votes.

But it’s not only about registering younger residents to vote, Michigan has to increase the number of younger residents who actually vote. Statistics from the Michigan Department of State in June showed that while many young people are registered to vote in Michigan, there is a significant gap between the number of registered voters and those who actually voted. In the last presidential election in 2020, over 1.4 million eligible Michigan youth were registered and only about 864,000 voted, a difference of 38.3%.

Among preregistered CHS students, senior Jupiter Gergics is eager to participate in elections. Even though they won’t be 18 by the presidential election date, Gergics still passionately shares their opinions and is looking forward to when they get a vote. One of the topics they feel most strongly about is abortion rights.

“The possibility of having a life inside my body that I don’t want to have [is] just honestly terrifying,” Gergics said. “I think it’s really stupid to govern that choice for other people when you can’t possibly understand their situation as well as they do.”

Gergics understands the power held by politicians: their ability to make choices for citizens, unbounded except by elections. Gergics’ family immigrated to the U.S. shortly before former President Donald Trump was elected into office. Their family had not yet secured green cards and were scared that Trump would enact anti-immigration policies before they were safely situated in the country. This ignited Gergics’ interest in participating in local and national elections. They will vote to protect other families from deportation.

Senior Rebecca White will vote in the 2024 election to protect women’s reproductive rights. White has paid special attention to certain candidates this year to keep herself informed on key issues. She was incensed at the overturning of Roe v. Wade and plans to vote for candidates who will secure female bodily rights.

“We need to get the word out,” White said. “We need to make changes in our community. We’re the next generation of people that are going to be able to do that.

White registered to vote online from the Michigan Secretary of State’s website with help from her parents. She found the process simple and fast to complete. Having the means to vote in the upcoming presidential election makes White feel in control of her future, knowing that her voice and vote matter. She encourages her peers to tune into the news and find out where each candidate stands on the issues that they care about.

White, Gergics and Shink agree that abortion rights are a key issue in 2024.

“If you look at what’s happening in Texas or Georgia, people are dying because they are not able to access the medical care that they should have because of the extreme abortion bans and Trump could, with the stroke of a pen, make that the law of the entire country, in spite of all the work that we’ve done to protect freedom here in Michigan,” Shink said.

How can people protect these rights? Shink believes that the answer is voting. Michigan Democrats have pushed to expand voting access, including through preregistration. Increasing voting rates also improve the accuracy of state representation in the legislature.

“What’s going on in Lansing is addressing real people’s needs in a way that hasn’t for a really long time because of fair districts,” Shink said. She hails from a family with split party affiliations, a rising trend Shink has noticed for many years.

“When I was younger, we had a governor, William Milliken, who was a Republican,” Shink said. “He was uniformly loved and did things like protect the environment, protect women’s rights and make sure that people had access to good jobs. That’s not something that Republicans are interested in doing at this time, and [they] are making it a lot harder for Democrats to be able to do those things as well, although we are doing them.”

Shink finds that the growing chasm between the two dominant political parties in Michigan nurtures “radicalized” perspectives over informed voting. By boosting registration among younger voters, Democrats hope to hold onto control of the state House of Representatives into 2025.