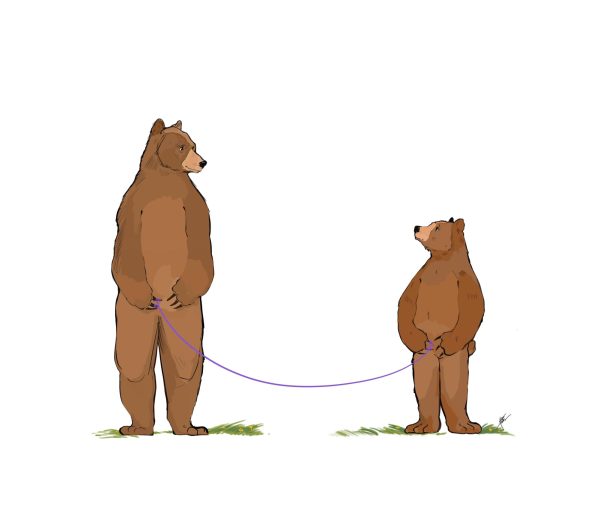

Defining Family

Originally Published Nov. 1, 2012:

A kindergarten classroom is plastered with posters of counting numbers, the ABCs, and in the middle, stick figures of a mom, dad, sister, brother, dog and cat titled, “My Family.” This may be our traditional family image, but the simple drawing wouldn’t be enough to represent the families of Lauren Hall, Ann Arbor resident for 25 plus years, or Community High School sophomore Lashay Ellis.

In the early 80s, Hall and partner Shellee Almquist knew that they were ready to have a family. Initially they started by contacting every adoption agency in Michigan, just like many other couples they knew.

The difference was they wanted to be completely open as a gay couple. Besides being open with each agency, both Hall and Almquist felt they needed to be open with their families too. Hall had struggled in the past with coming out to her family in fear of losing her relationship with her little brother and being disowned by her parents. Finally, Hall wrote a letter to her mother and father.

Hall was very straightforward. “We are going to have a family and you can choose to be a part of it and be grandparents or not, but this is who I am, this is what I am going to do—so take it or leave it,” said Hall.

Hall’s father’s reaction was much like she expected. “My father said that if you would have told me eight years ago, I would have disowned you and never allowed you back in the house but I sort of thought this was who you are and I searched in my soul and decided you are still my kid. I love you and I want to be the grandparent to your children.” Hall believes they are not really supportive but tolerant.

Even without the full support of Hall’s parents, the honesty of their relationship status was still very important to the couple when adopting. “We wanted to be very open about who we were because we wanted our kids to feel like this was their normal and it was okay, so we didn’t want to have any negativity to it at all,” said Hall.

The laws were not in their favor and they were unable to adopt at that time due to custody rules.

Hall and Almquist wouldn’t give up so easily. After discussing different options,

like using friend donors and lying about their sexual preference, the couple

decided on artificial insemination. “It was fairly difficult to find a doctor who was on board and who would let us go on with the process being a lesbian

couple,” said Hall. “At that time, it was an uncharted territory.” Almquist, in this way, delivered two baby girls, Zoe and Zane, four years apart.

Even though Hall was beside Almquist through the whole pregnancy, she had no legal status as a parent to Zoe and Zane. Hall wanted to be a an adoptive parent. Hall and Almquist made many trips to the courthouse to fight for their right. The couple had safe houses for their children just in case the courts decided to take them away due to custody laws. Luckily, it never came down to that.

Continuing to fight, Hall and Almquist went through with the adoption

process so they could both legally be parents. Once they finally got to the last steps, the state refused to change the birth certificate from mother, father to parent one and parent two. “I refused to be listed as the father so there was a whole bunch of us [other gay couples] who were able to do the whole second party adoption,” said Hall.

The father label wasn’t going away. “Pretty much everything was great until they [Zoe and Zane] started school. Once you are in the school setting it is so very heterosexual and heterosexist,” said Hall. Zane said every year in elementary school she was forced into making a father’s day card. The family felt they were challenged by the education

system but still continued to be very out and affirming. Many parents were fine with their status but some weren’t. A few of their classmates weren’t allowed at their house for playdates and one mother took her child out of Zoe’s elementary class.

There was also times in early elementary school that “fatherly homework,” was assigned. If the kids felt left out, Hall would give them an option to call their grandpa or uncle to participate.

“There was no boohoo. That is a fact. There is no dad involved,” said Hall.

It wasn’t till Zoe and Zane got older that they realized all their peers weren’t in support of their homelife. “It took till middle school to get harassed and hear the language, ‘Fag’ and ‘that’s so gay’. I know that was the point at which they became closed up and weren’t as open about their family and having two moms,” said Hall.

Zane and Zoe believe that having two moms shaped them as having any loving parents would.

Lashay Ellis, the CHS sophomore, is also mostly unfamiliar with the traditional

mother-father dynamic. She only experienced that for a year of her life.

At age one, her parents got divorced and her father moved out. “I was really

young so I never really remember getting the chance to live with my dad,” said Ellis. But he didn’t move too far. He now has a seven year old son. Ellis said they talk to each other on the phone every single night and she spends her weekend with him.

Soon after, Ellis’s mother remarried to a new man. Four years later, Ellis had a new baby brother.

Ellis’s new family lived together for only five years before Ellis experienced another change. Ellis’s stepfather and half-brother packed their bags and moved to North Carolina. Her stepfather left with a new fiance. “My mother believed it was the right decision for my brother to follow as well,” said Ellis. Ellis still tries to spend her Thanksgiving, Cshristmas and a handful of her summer with her half-brother. This summer, Ellis spend a chunk of her summer relaxing in North Caroline beside him.

From then on Ellis was raised by a just a single mother. “We are really, really close. I seem to tell her everything,

I mean not everything because we know each other’s limits,” said Ellis. Until three years ago, Ellis was used to a quiet household where her only chore was doing the dishes. Now Ellis has a lot of babysitting to do; she has a three year old baby sister.

Transitions seems to be a normal thing for Ellis. “But the hardest thing though is not having everyone together at one time,” she said. “I have to follow a schedule to make sure I see family members. I just wish all my siblings could be in one house together.”

For both Ellis and Hall, the poster on the kindergarten wall fails to capture the reality of family.