Attorney Ritchie Talks About the Police Brutality Not Talked About

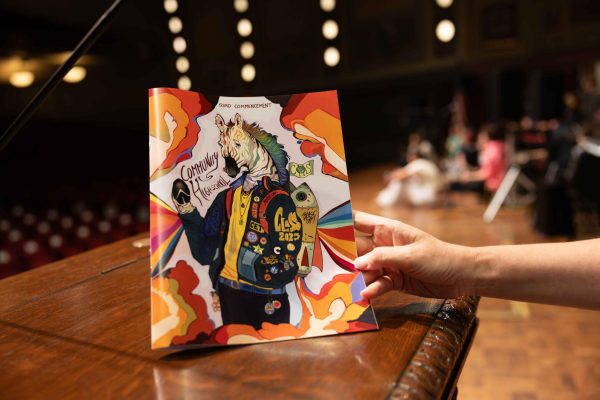

Speaker Andrea Ritchie standing in front of a listing of names of black women killed from police brutality. With her book “Invisible No More” and her talk, Ritchie is working to “[counter] the invisibility of the names of black women who will never make it to a prison cell:” those murdered by our police force.

“What comes to mind when I say racial profiling?” Andrea J. Ritchie asked. “Or police violence? Or police brutality?”

Huddled in Hatcher Graduate Library, a captivated audience sat and listened to Andrea J. Ritchie – a renowned, attorney, author, and researcher of policing – on Thursday, Jan. 18. After recently publishing her own book, “Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color,” Ritchie was invited to speak at the University of Michigan as one of the many lectures held in honor of MLK.

After asking rhetorical questions to open up her conversation, Ritchie described the typical image that she says is most often associated with police brutality. She described the image commonly seen in major newspapers, the image that sparks national outrage: a black man being mistreated by a white policeman.

However, Ritchie was not here to talk about that. She talked about the not reported on injustices, specifically, the cases of police brutality against black women, LGBTQ+ women, and black LGBTQ+ women. This type of police brutality is common yet, Ritchie argued, is far less recognized.

She also talked about “broken-windows policing,” based on the theory–which is widely disputed–that cracking down on small crimes will prevent serious crimes from happening, and how it is used as the basis for unjust violence towards vulnerable people (women, minorities, people with disabilities or people of low socioeconomic status.) For example, when Staten Island police put Rosan Miller, a seven-month-pregnant woman, in a chokehold in front of her five-year-old daughter for committing the crime of barbecuing on her front porch on July 27, 2014.

Near the end of her lecture, Ritchie focused on a story especially relevant to the university she was visiting.

“How many of you have heard about Aura Rosser?” Ritchie asked. She smiled at the substantial amount of raised hands in the room. “That’s because this is Ann Arbor.”

Aura Rosser was an artist. She was a mother of three. She was a victim of child abuse. She was a victim of domestic abuse. She was shot by the Ann Arbor police within ten seconds of them arriving to her home after being called by Rosser’s partner in Nov. 2014.

Some reports claim she had been charging at an officer with a knife when she had been shot, which may be true, although she was fifteen feet away from the officer when she died and carrying a four-inch fish knife.

Many reports mention Rosser’s mental-illness.

Since slavery, black women have been painted as being inherently violent, unstable, licentious, or mentally ill. Such characterizations were used to justify holding them as slaves, Ritchie said. If a woman widens her eyes or stiffens her body, those are enough to classify her as dangerous.

This historic demonization of black women, “is still playing out hundreds of years later when police officers answer a call to help.”

As she finished her lecture, Ritchie brought up how she had put off writing her book about police violence against LGBTQ+ women of color for awhile. “I didn’t write this book, because I thought someone else would.” Ritchie said, “Someone with less privilege, someone with more experience.”

But no one else wrote the book. So she did.

“This is not something someone else has to do,” Ritchie said, referring to fighting for justice. “We need to come out and figure out responses.”

![Speaker Andrea Ritchie standing in front of a listing of names of black women killed from police brutality. With her book "Invisible No More" and her talk, Ritchie is working to "[counter] the invisibility of the names of black women who will never make it to a prison cell:" those murdered by our police force.](https://chscommunicator.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/DSC_0862-e1517499944533-900x530.jpg)