Ann Arbor lawyers fight for Muscogee Creek rights

A mere six feet was all that stood between Ann Arbor lawyers, Riyaz Kanji and David Giampetroni and the eight most powerful justices in the country.

“You could hear the justices breathe,” Giampetroni said.

It was a long and winding road that took the attorneys from the Kerrytown office of Kanji and Katzen all the way to the highest court in the land — the United States Supreme Court.

As a young attorney starting out, it was Kanji’s interest in civil rights law that led him to accept a job working for a firm that represented American Indian tribes.

From this beginning, Kanji’s passion for defending American Indian rights drove him to start his own firm specializing in representing tribes across the United States. With offices in both Ann Arbor and Seattle, Kanji and Katzen has represented tribes in all corners of the country. However, they had never represented any tribe based in Oklahoma.

That is until a young lawyer named Philip Tinker, from Pawhuska, Oklahoma, joined their team. Tinker, a member of the Osage Nation himself, came to the firm having taken a special interest as a law student in the murder trial of Patrick Murphy. In 1999, an Oklahoma jury found Murphy, a member of the Muscogee Creek Nation, guilty of the murder and mutilation of another member of the Creek tribe, and sentenced him to death. When Murphy appealed the ruling, what started off as a grotesque yet straightforward murder became so much more.

The basis for the appeal dates back to 1830, when then President Andrew Jackson approved the forced relocation of thousands of American Indians living in Alabama and Georgia, known in the history books as the “Trail of Tears.” Government troops burned civilizations to the ground, murdered livestock, and rounded up every soul in sight. Those who did not cooperate were shot in cold blood.

One of the tribes subjected to these atrocities was the Creek Nation.

For those fortunate enough to survive the brutal journey, Congress assigned the Creeks and four other American Indian Nations tracts of land, “The Indian Territory,” in what is today within the boundaries of the state of Oklahoma.

In 1901, the federal government attempted to break up all Indian Reservations into individual plots of land, in order to allow non-native settlers to take over. The Creek Nation resisted these efforts but did permit non-natives to settle in certain parts of their territory. Most importantly, the Creeks never relinquished their status as an Indian Reservation.

When Oklahoma became a state in 1907, settlers came in by the masses with no regard for the boundaries of the Creek nation.

This historical background provides the basis for Kanji and Giampetroni’s appeal argument. In determining jurisdiction in American Indian cases, three factors must be met: the accused must be an American Indian, the victim must be American Indian, and the crime must have been committed on reservation land.

“The first two are definitely true: He is a Creek, and he murdered a Creek,” Kanji said. “That made the central issue of this case whether this Creek reservation exists or not.”

Tinker first brought the case to Kanji’s attention while it was awaiting trial in the Oklahoma 10th District Court of Appeals. Kanji initially declined to partake in the case, however, Tinker persisted.

“Over the course of a couple years, he was basically in our offices once a week saying, ‘Can we do the case?’” Kanji said.

In 2016, the Supreme court heard a case addressing the question, ‘what does it take to disestablish an Indian Reservation?’

The Court ruled that only Congress could disestablish an Indian Reservation, and it needed to do so explicitly. “The Supreme Court adopted, essentially, the arguments that [Tinker] had been pressing to us in our office and that he’d been pressing since law school,” Giampetroni said.

Kanji decided to join Murphy’s case by representing the Creek Nation as a third party, in what is formally known as an amicus curiae.

After months of preparation, Giampetroni stood on the floor of the Oklahoma 10th Circuit Court and presented the argument that the crime had been committed on the Creek Reservation and therefore was subject to Federal or Creek Nation jurisdiction. Despite what they viewed as long odds, Giampetroni and Kanji prevailed on behalf of the Creek Nation.

“When we won, people were calling us and saying, ‘How did you do it? How did you win?’” Kanji said. “It was unbelievable because there had been this assumption that there were no reservations left in this part of Oklahoma.”

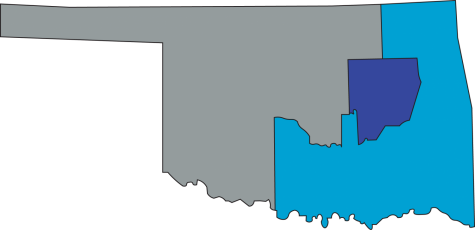

For Kanji and Giampetroni, the elation of victory was quickly followed by the realization that the State of Oklahoma would attempt to appeal the decision to the Supreme Court. At stake in this decision is not only the recognition of the Creek Nation and all the land that goes with their reservation, but the recognition of the other tribes in Oklahoma and all the land that went with their reservations as well.

“Suddenly, just by the virtue of this case, the non-Indian population living on a reservation went up by a factor of five,” Kanji said. “The 200,000 people who are not Indians living on reservations all of a sudden became 1,000,000.”

In total, these reservations make up almost 50 percent of Oklahoma.

On June 8, 2018, Kanji got the official order that the Supreme Court would be hearing the case, and the Kerrytown firm immediately got to work.

“One of the things that we got to do in the Supreme Court that we didn’t have time to do in the 10th Circuit was really mine the history,” Giampetroni said. The team read countless documents, transcriptions and manuscripts from tribal leaders as well as those of Congress, in an attempt to decipher the true intent of past legislation regarding the Oklahoma Reservations. In addition, Kanji and Giampetroni traveled to Oklahoma to experience the ins and out of the Creek Nation’s government.

After six months of nonstop preparation, the day finally arrived. While Kanji was no stranger to the court, having been a clerk to Supreme Court Justice David Souter, this was his first time arguing in front of the justices.

It is standard that the amicus curiae speaks last in such cases leaving plenty of time for the attorneys’ anticipation to build.

The countless hours of preparation boiled down to a ten-minute time cap to present their argument.

Giampetroni explained how the justices’ initial line of questioning would likely give clues as to whether they found their argument convincing or not.

“For us, it was interesting because we had both,” Giampetroni said. “We had justices expressing skepticism of our views, and justices expressing strong support.”

As soon as he stood up Kanji had no time to be nervous. Having memorized enough facts and stories to continue his argument for over five hours, the most challenging part of the day was expressing his thoughts in as little time as possible.

“It doesn’t come naturally to me because I like to talk, but in that situation I was just trying to be really focused,” Kanji said.

When it came to Kanji’s argument, he took a different approach from the attorneys that preceded him.

“Every other lawyer, and these are good experienced lawyers, was making speeches, they were arguing, they were debating,” Giampetroni said. “[Kanji] got up there and his tone was totally different. It was, ‘let’s just talk about it,’ and he had a conversation with them. It was really remarkable.”

The consensus from the Kanji and Katzen attorneys in attendance was that their firm delivered a convincing and compelling argument in support of the Creek Nation’s claim to reservation land in Oklahoma. It will be several months before the Supreme Court releases its decision, but win or lose, these Kerrytown lawyers have surely represented the firm of Kanji and Katzen proudly.