Pandemic Causes Hospital Overflow

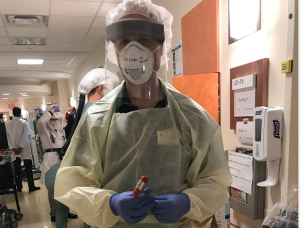

The emergency department (ER) of the Huron Valley Hospital in Commerce Township, Mich. has 28 beds. Throughout the pandemic, up to 24 of those beds have been filled with COVID-19 patients—patients who wouldn’t otherwise be there. This surge of additional patients has overwhelmed Huron Valley and hospitals around the country, and forced medical professionals to adapt.

Dr. Matthew Compton has been an emergency medicine physician for over 20 years. At the beginning of the pandemic, the Huron Valley Hospital, where he’s employed, actually saw a decline in patients, due to widespread fear of infection which caused many individuals to delay treatment or seek it elsewhere out of concern that going to a hospital would put them at increased risk.

These fears certainly weren’t without reason, as hospitals continue to be flooded by COVID-19 patients. The concentration of infected individuals created an environment where the disease could potentially spread rapidly. The Huron Valley Hospital tests rigorously, and continual screenings are carried out from the moment a patient comes in for treatment.

Any individuals showing any COVID-19 symptoms are separated, and are treated in specially designated areas: usually isolated from the rest of the emergency department and equipped with rigid doors.

Over the past 12 months, any patients being hospitalized or undergoing surgery have been tested for COVID-19. At first, this policy seemed excessively cautious to Compton, as most viral respiratory diseases are highly symptomatic, but a large number of asymptomatic patients marked this as a very different situation.

“[It’s] certainly been difficult throughout the entirety of the pandemic [that] there are a lot of people, for whatever reason, who can end up getting exposed [and] becoming infectious, although they may not necessarily have any symptoms themselves,” Compton said. In fact, many patients have come in for other procedures, emergency or otherwise, only to find out they’re infected with COVID-19.

“Many, many more than I would have ever expected,” Compton said, regarding the number of asymptomatic cases that are discovered when patients are procedurally tested. The testing is incredibly sensitive, and can obtain a positive result even months after the timeframe in which a person is infectious, which creates another difficulty.

The problem facing hospitals generally isn’t physical space. The Huron Valley Hospital has an entire in-patient unit—with some 20 beds—that’s closed because it simply doesn’t have the nursing staff to care for those patients. The shortage of medical personnel, particularly nurses and respiratory therapists, is a much more severe issue and is having a widespread impact.

“Unfortunately, this is probably not a good event to draw more people into those fields in the future,” Compton said. “So, this could have some pretty long-lasting ramifications because of that.”

These staffing shortages have been one of the primary driving forces behind increasingly lessening quarantine regulations. In the early days of the pandemics, medical personnel with any sort of exposure were required to quarantine at home for two weeks, which created worker shortages of varying severity. As further information was gathered regarding the COVID-19 virus, and following the rollout of vaccinations, it has become reasonable for a fully-vaccinated employee to continue to work following exposure.

“Even with infections, there’s a fairly quick turnaround time, that is according to the guidelines,” Compton said. “It seems like because of [the limited available staff] there’s an even lower threshold to be able to return to work.”

Despite adjusted guidelines, hospitals continue to find themselves short-staffed. The nursing staff at the Huron Valley Hospital simply can’t keep up with the surplus of patients. They’ve had to revert to putting patients in shared rooms—though only if both patients have tested positive for COVID-19, eliminating the risk of transmission. However, these adjustments can’t account for the sheer number of patients.

“If, say, there aren’t enough nurses to take care of patients in the hospital, what they do is they leave those patients in the emergency department,” Compton said. This influx of patients puts significant strain on the emergency department, and compromises the efficiency of the department.

“[Patients] may come to the hospital by ambulance and then they get put out in the waiting room and potentially could wait several hours before they ever get seen,” Compton said. This delay of emergency treatment presents a clear problem, but not a clear solution.

Overwhelmed hospitals can’t just start turning away patients in need of medical care. Even if a hospital were to close its doors to incoming traffic, it would still need to go somewhere.

“With an event like this, effectively all of the hospitals in the area are in the same boat as far as being overwhelmed,” Compton said. “If one particular hospital says, ‘oh well, we can’t take any ambulance traffic,’ [then] the next hospital will do that and the next hospital will do that, and then eventually everyone would be on the same level ground and ambulances would just start bringing patients in anyways, and say ‘tough luck.’”

Further exacerbating the problem, COVID-19 patient hospitalizations, particularly with the Delta strain, were considerably extended from average hospitalizations: typically lasting four to five days.

“The people that ended up getting hospitalized would end up being in the hospital for two or three or four times longer than what an average hospitalization would be,” Compton said. “This patient population that was being admitted with COVID-19 would end up being in the hospital for 12, 15, 20 days.”

The recent Omicron variant has not resulted in the same lengthy hospital stays but presents its own host of problems for the public. For hospitals, things have remained largely the same. The Omicron variant is highly transmissible—meaning more cases—but also less virulent—reducing the percentage of people who have a serious illness. However, the tendency to underrepresent its severity is dangerous.

“There’s been this underpinning by a lot of people to say, ‘you know, this is just, you know, a bad cold, it’s like having the flu,’” Compton said. “But the reality of it is that even with the decrease in severity of cases, the mortality rate for this is at least ten times higher than the mortality rate associated with influenza.”

The people typically dying from influenza are generally the older, and the immune-compromised. Although COVID-19 is also more dangerous to these groups, it is also threatening to a much more unpredictable demographic.

“Not only are those same [immune compromised] people being affected, but along with every one of those people that dies, there are nine, ten, eleven other people who really don’t have any sort of severe medical conditions that are putting them at risk that are dying also,” Compton said.

Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of hospitalizations are unvaccinated individuals, but beyond that, there are no clear commonalities between those who suffer extreme symptoms and those who are largely unaffected.

“There’s not really been any compelling risk factor as far as people having severe illness outside of being unvaccinated,” Compton said. “You may take two different people that really don’t have a lot of other medical issues otherwise, and have someone who effectively goes through their illness and never even realizes that they’re sick, and you can have someone that has their lungs completely fail on them.” There is no clear distinction between Person A and Person B that causes one to become viciously ill and one to be completely free of symptoms. And it is this rather ambiguous group that will be making up those nine to eleven deaths additional to the expected ones.

“Statistically, it’s still a fairly small percentage of the population that ends up getting severely ill and ends up dying from this, but the reality of it is that at this point we’re, it’s a lot of people when it all gets added up,” Compton said.

There have been instances when it seemed to Compton as though the situation was on track to significantly improve “in a few months,” or “by the end of the year,” but the continued presence of the pandemic has shown this to not be the case.

“The staying power of this infection has been pretty amazing and discouraging all at the same time,” Compton said.